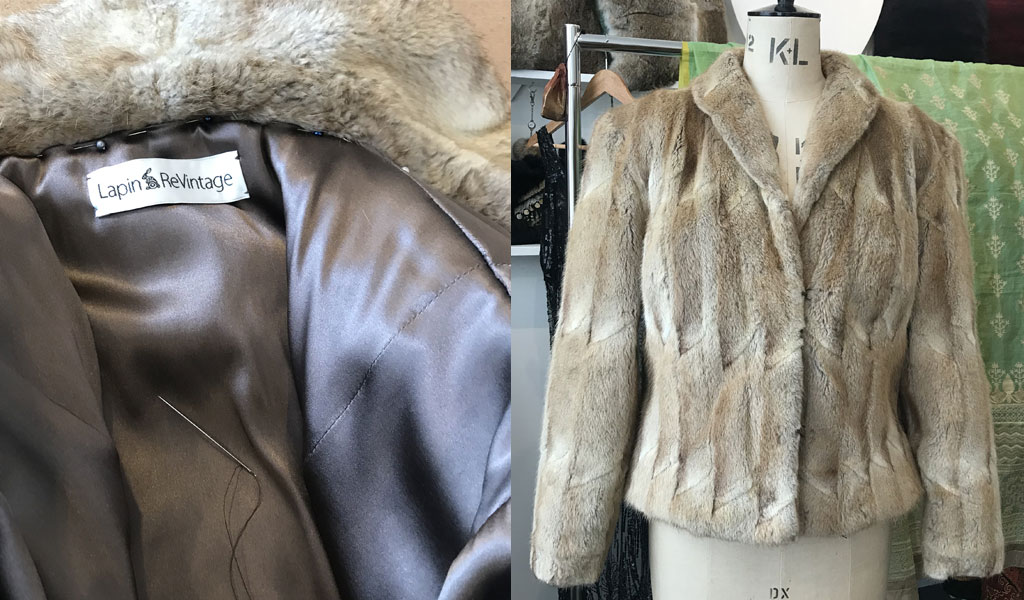

Jane Avery is a couture designer from Dunedin, New Zealand, known for her bespoke garments combining exotic fabrics with wild rabbit fur. Her label is Lapin (French for rabbit), and her ethos is “eco-couture”, reflecting the fact that rabbits are a major pest in her part of the world. Now she has launched a new label, Lapin ReVintage, which is all about repairing, restyling and repurposing vintage fur. Since so little has been written about this niche market, Truth About Fur set out to learn more.

SEE ALSO: New Zealand designer embraces wild rabbit “eco-fur”. Truth About Fur.

Truth About Fur: Are Lapin and ReVintage two separate lines, or do they dovetail together?

Jane Avery: They are both meaningful to me in their own ways, but they sit comfortably together. For example, when I receive a ReVintage commission, I may be repairing the garment in its original form, or I may be taking parts of the fur and incorporating them into a new Lapin ReVintage design. There’s enough fur in a vintage cape or stole to make a collar and cuffs for a coat of merino wool, Indian silk or another beautiful textile.

Prolonging the life of any garment is good for the environment, just as using the fur of pests is. So it’s all “eco-couture”.

TAF: Bloggers say that recycling old furs took off in the first Covid-19 lockdown, when we all decided to clean out our wardrobes. But now all our wardrobes are clean, so is it a passing trend?

JA: No, it’s more than a trend. It’s part of a groundswell of people wanting lifestyles that are kinder to our planet. That started before Covid and will outlast it too.

People have various reasons to extend the lives of vintage furs, not always related to lifestyle. Of course they appreciate the beauty, resilience and warmth of fur, and a vintage piece can be a great reminder of its original owner, perhaps a beloved grandmother. But there are other motivations that reflect our changing attitudes towards the planet.

Seeking sustainability is one. We are increasingly rejecting wasteful consumerism, and that includes “fast fashion”. We want to buy fewer clothes, better quality, and make them last. The “Three R’s” – repair, restyle, and repurpose – are part of this, and are in vogue!

SEE ALSO: The sustainability of fur. Truth About Fur.

Another motivation concerns the morality of taking animal life for food and clothing. Some people, for example, consider it abhorrent to farm new fur, but hate to waste the fur of an animal that’s already died. I see something similar working with wild rabbit fur; some people won’t wear farmed mink, but are happy to wear the fur of pests that are being eradicated anyway.

And some people, like me, have a cultural motivation. Every vintage fur that lands on my work bench has a story, and is its own tutorial on garment construction. As I dismantle it, it reveals secrets of the furrier’s craft, honed over hundreds of years. So we are driven to preserve the craftsmanship that goes into working with fur.

TAF: So is there such a thing as a typical ReVintage customer?

JA: Perhaps the most common motivation of customers is wanting to display an heirloom fur they received from their mother or grandmother. They may want to wear it or repurpose it as a couch throw or cushions, but the important thing is to feel connected to a loved one. For these people, it’s all about remembrance and emotion.

But that’s not always the case. For example, a man brought in a pristine, full-length ranch mink coat he’d picked up at an estate sale for $150, and wanted it turned into a couch throw. It was a beautiful flared coat with very skilful stranding work extending from neck to mid-calf, and a lady’s name sewn into the silk lining. The hems were full of sawdust, a sign it had been drum-cleaned, and judging by the perfect condition, temperature-stored. A part of me felt mortified to be carving into this work of art, but unless it went to a museum or couture collector, it had outlived its usefulness as a coat. Sadly this is the fate of some vintage furs these days. But the throw I made from it was gorgeous, so I hope it’s being enjoyed!

TAF: What problems do you face most when working with vintage furs?

JA: New or old, fur is a forgiving material. New fur can be deftly manipulated if there is damage or there’s a mistake during the making process. And if you find a disaster zone in an old fur, it usually just requires a bit more negotiation.

Plus, fur garments are built to last, so most vintage furs are perfectly useable, even after spending decades in the back of a wardrobe.

But of course they do get damaged, and a common problem is tearing, either along stitched seams or in the general skin area. Some tears are nice, straight lines, while others are messy affairs going in several directions. How to deal with them depends on the condition of the skin. It may be hard and brittle, or soft and disintegrating.

Separated seams are the other common damage. When possible, I’ll stitch them back up by machine, but sometimes the needle perforations just create a new line that tears readily. Then it’s out with the needle and thread, pulling the edges gently together with big stitches, and then sports tape, which is made to stick to skin, after all.

When I return a coat to its owner, it may appear like I’ve worked a little magic. But perhaps – and this is a last resort! – I just pinched a bit of fur from an unseen part of the coat and literally pasted it with fabric glue onto a disintegrated section that’s been reinforced from behind. It’s a methodical and intuitive process that involves judgement, an experienced eye, and a certain amount of chutzpah.

TAF: So can all furs be saved?

JA: If a coat is shedding badly, there’s not much that can be done. So now and then I have to tell a customer they’re dreaming, and all we can do is turn the best bits into cushions. But my motto is “work with what’s in front of you”, so I rarely turn a job down. If a person is emotionally attached to a fur, then it’s worth restoring or repurposing as best I can.

That said, I sometimes restore a coat and return it with strict instructions on how to wear it. Sit and stand in it nicely, I say, and do not wear it while driving or lounging on the sofa!

TAF: How about the different fur types you commonly see? Are some easier to work with than others?

JA: I see a lot of vintage rabbit since it was so popular here in the past, often cut and dyed to mimic other fur types. Old rabbit skin is surely not the most robust and is frequently delicate, but it can still be beautifully supple and suitable for machine-stitching. I’ll probably tape the repaired seams and some of the original ones for safety, and instruct the owner to “handle gently”.

Muskrat fur was also popular before, but it doesn’t survive the years well. It’s very likely to be brittle and ripping, and only salvageable with hand-stitching and tape.

Vintage mink skin is often in very good condition and easy to handle, but fox can be very thin and rips easily.

I’ve also worked with vintage chinchilla rabbit, fitch, weasel, marten and possum, but perhaps my favourite were three gorgeous coats, over 70 years old, that I think were Siberian flying squirrel. They were delicate in places, but the skin was supple and the lustrous fur all intact.

TAF: How about the future? You describe interest in recycling vintage fur as part of a “groundswell”. So can we expect growth?

JA: For clothing in general, the “Three R’s” – repair, restyle, and repurpose – are already growing fast as part of a shift to more sustainable living. But in New Zealand at least, using fur for clothing is just a small part of this. It’s not cold enough, plus the anti-fur lobby has been quite effective. There’s only a small market here now. The last traditional furrier in the entire country, and my teachers, Mooneys Furs of Dunedin (est. 1912), closed in 2020. As a result, craftspeople skilled in working with vintage fur coats are now a rare breed. As one of those rare artisans, I encourage anyone to ReVintage their furs. The results are very satisfying.

In colder countries, where fur is a way of life and there’s a steady supply of vintage materials to work with, the outcome could be very different. If you have the skills, setting up as a recycler of vintage furs could be a really good business opportunity!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.