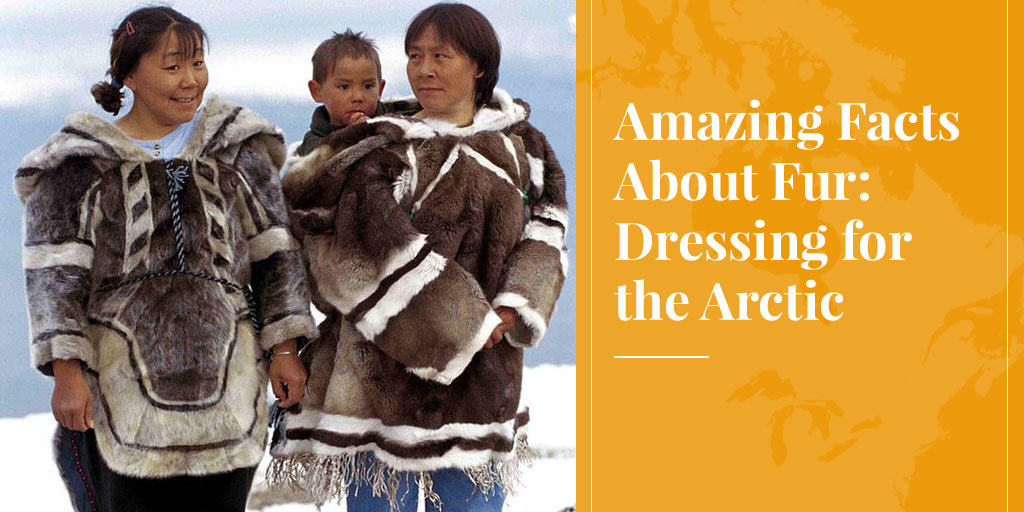

Ask most people what fur is good for and they’ll say it keeps the wearer – animal or human – warm. True enough, but some types of fur are so much warmer than others, and the reasons why may surprise you. In this first of a series to introduce some of the amazing facts about fur, we’ve planned a hunting and fishing trip and now it’s time to plan our wardrobe. We’re headed to the Canadian territory of Nunavut, and we need to dress for the occasion!

Nunavut is actually the size of Western Europe, so even though almost the whole territory is classed as having a polar climate, there are considerable differences in weather and hours of sunlight. Time of year also makes a big difference. So let’s narrow it down and say we’re headed for the capital of Iqaluit at 63°N, in late March.

We’ll have about 6 hours of sunlight a day, enough for some good hunting or fishing close to home. But with average temperatures for March at -28°C, and a record low of -44°C, we can forget our birdspotter’s anorak. Heck, with wind chill factored in, the mercury once hit -62°C, so you might be tempted to leave your entire wardrobe at home, but don’t. Jeans and sneakers will get a lot of use when we’re not actually out on the land or ice.

It’s time to plan our new wardrobe and then figure out how to get it, because it’s not going to be from your typical downtown furrier. Mink, fox or chinchilla are not up to the job, plus we’d prefer not to run up a huge cleaning bill on our return.

What we’re after is fur that’s full of holes.

Hollow Hairs Please

One of the key functions of fur in nature is thermoregulation: helping furbearers stay cool in hot weather and, more importantly, warm when it’s freezing. This is achieved primarily by means of insulation, and one of the greatest insulators is air. Or, to be more precise, trapped air.

Heat travels more slowly through air than through solids or liquids, (For comparison, water is 24 times more effective at conducting heat than air.) Furbearers take advantage of this by trapping air between the dense hairs of their underfur, then sealing it in with their long guard hairs. For us humans, it’s a case of dressing in layers: two thin sweaters, with a layer of air between, keep us warmer than one thick one.

But some furbearers, mostly species of deer, have taken it to the next level. Not only do their guard hairs help trap air in the underfur, but those guard hairs also have air trapped permanently inside each one! Commonly known as “hollow” hairs, think more in terms of a honeycomb center, with countless tiny pockets of air. (Click here for an example of a scanning electron micrograph of red deer hairs.)

So we’re going to go with a local favourite in Nunavut, caribou fur.

Caribou must endure bitter cold for months at a time, and they don’t even shiver. How do they do it? It’s not all in the fur; a highly efficient means of minimising heat loss known as countercurrent heat exchange functions in their legs and nasal passages. But the key is their winter coats, three inches thick and covering them from nose to hooves, all topped off with those hollow hairs. (Interestingly, it is also these hollow hairs that cause caribou to swim so high out of the water, further conserving heat.)

So we’ll start with a couple of knee-length parkas, not for alternate days but to wear as a pair if needed. The outer parka, worn on its own with the fur on the outside, will be for less cold weather or trips close to home when a sudden change in the weather just means a sprint home. The inner parka will be added, with the fur facing our body (yes, we’ll need a shirt or other kind of lining!), when the mercury plummets or we’re traveling farther afield.

Since we’re not dressing to impress but looking for utilitarian wear, we’ll go with plain parkas, not the decorated versions commonly associated with Inuit culture. Caribou hair sheds easily and the hollow shafts are constantly breaking, so decorated parkas are for special occasions only (and for sale to tourists).

And since it’s not mid-winter, we’ll go with summer caribou skins, which are also those generally used for garments. The hair is shorter than winter skins so they’re not as warm, but this also makes them less prone to shedding. Summer skins are also easier to dress than winter skins, and while dressing is said to reduce warmth, it does make them more durable.

And if you’re ready to go totally native, caribou pants and socks come next, both with the fur on the inside, then caribou mittens and kamik (traditional footwear) to round off your ensemble.

A word of caution though. Unless you’re actually out on the land or ice, dressing head to toe in caribou will make you stand out from the crowd. Plus, propping up the bar in Iqaluit will very quickly cause you to overheat! That’s where the jeans and sneakers come in.

Hydrophobic Hood

Before you shell out for your parkas, though, pay particular attention to their most important feature: the hood lining. It must be hydrophobic.

OK, we don’t literally want it to be “hydrophobic” or it would be scared of water. What we want is a strong “hydrophobic effect”, meaning it appears to repel water. (There is no actual repulsion involved, just an absence of attraction.)

The hydrophobic effect can be found everywhere and is essential to life on Earth. Observe a droplet of dew on a leaf. The water and the leaf want nothing to do with each other, to the point where the dew forms a sphere. The hydrophobic effect is also seen in all fur, but some types are more hydrophobic than others.

And why is a hydrophobic hood lining so important? Well, here’s what happens if you don’t have one. You’re out one day when a blizzard blows in and the temperature suddenly drops to -30°C. You pull up your hood with its big, fluffy synthetic lining and laugh at Mother Nature. Next thing you know, your breath is freezing on the lining which then freezes to your face. Lesson learned. You’ll never wear a synthetic hood lining again, at least not in the Arctic.

Better to do it right the first time and go with the ultimate in hydrophobic hood lining, wolverine fur. Since that is not always available, northern grey wolf makes an excellent second choice.

Nature’s Raincoat

But we also need a second outfit, still for time on the land, but for days when caribou will make us feel like a baked potato. The sky is clear and the forecast is for temperatures around freezing. There’s a chance of rain and slush underfoot, so being waterproof is paramount. It’s time for Nature’s raincoat, sealskin.

People from down south often assume sealskin must be the ultimate in cold-weather clothing, but it’s not the case, and that’s because the species used – mainly ringed seals, as in Nunavut, and harp seals – have no underfur. Sometimes known as “hair seals”, their pelts are composed entirely of short, shiny guard hairs.

The “flat” fur that comes from hair seals is not as warm as “true” fur (with underfur), like caribou, but it has some real pluses. Because there is no underfur, sealskin is light. It is also incredibly durable, more so than any other flat fur like calf or antelope (which is why it’s used to make rope). Its structure resists wind, its oil content repels rain, and its porosity allows it to breathe (which is why it also makes great tents).

And oh yes, it’s virtually waterproof, which is why it’s used to skin kayaks.

Sealskins, then, are the Arctic’s warm, wet-weather clothing, “warm”, of course, being a relative term. Mittens, a lighter parka, and most definitely sealskin boots therefore make it on to our shopping list.

Shopping Time

And now comes the hard part. It’s so hard, in fact, that if you’re planning a quick in-and-out visit to Nunavut, you’re not going to be wearing caribou or ringed seal anyway, so just pack the best of the rest. Unfortunately, buying an outfit of traditional Nunavut clothing is, like hollow hairs and hydrophobia, amazing – amazingly hard!

Forget about buying outfits off the peg, in Iqaluit or anywhere else. It’s not going to happen, though not for want of trying. Efforts have been made in Nunavut over the years to establish a garment industry with ensured availability from suppliers and standardised sizes and prices, but all to no end. The workforce with the necessary skills – older women, with kids to care for, working from home – have not taken to the idea of a production line.

So what to do? You can sign up for an expensive sport-hunting package and get the clothing, including a decorated parka made of dressed skins, thrown in. Finding someone to make it then becomes your tour operator’s headache.

Or you turn up in Iqaluit, ask around, negotiate hard, and be prepared to pay $1,500+ for a plain caribou parka, pants, kamik and mittens – and that’s summer skins, probably not dressed. If you’re staying a month, it should be ready by the time you’re heading home.

The good news is that Canadian harp seal garments can be bought on-line (here or here, for example), provided you don’t live in a country that denies you the freedom to import them. Which brings us to the last amazing fact about seal fur.

Nonsensical Bans

Almost all sealskin garments come from healthy populations of either harp seals or ringed seals. So healthy are these populations that the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies both harp and ringed seals as “Least Concern”.

And yet two of the biggest potential markets for seal products, the US and the EU, are closed for no good reason.

SEE ALSO: EU SEALING POLICY IS HYPOCRITICAL, ANTI-DEMOCRATIC

The US has banned imports of all seal products since 1972 under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, legislation that is fiercely defended by the nation’s animal activist community.

In the EU, the ban went into effect in 2009, since when the European Commission has made a pig’s ear of justifying it because it can’t. Everyone knows the ban was passed not for any rational reason, or even to satisfy popular demand, but because it was bought and paid for by lobbyists in Brussels working for animal rights groups.

Now, true to their reputation for feeble-minded solutions (like the bendy banana law), Brussels’ finest have sought to placate Canada’s angry Inuit by exempting them from the ban. Not surprisingly, many Inuit representatives have called the gesture colonialistic and racist, so we’ll see how that works out!

Truly, the politics of fur are no less amazing than the science and cultural traditions of this beautiful, warm and sustainable natural resource. Send us a postcard from Iqaluit!

My aunt has been thinking about getting some furs because she is planning to go to a really cold place for vacation but she wants to make sure that she is safer. Getting some help from a professional could be really useful and make sure that it will look really nice and be more comfortable. I liked what you said about how they will be able to trap heat between the underfur and hollow hairs that can be more effective.

Thanks for helping me understand that it would be best to dress up the right way for the Arctic to keep you from freezing up to your face. I will definitely look for the best clothing since we will be going there for my husband’s birthday. It is included on his bucket list that is why he badly wants it for his 30th birthday.

A clear concise and factual article explaining in detail without trying to excuse the right of indigenous people to live within their own culture without harming their environment ,concentrating on a sustainable source with a harvestable surplus.

The detractors of this way of life very often in my experience criticise from centrally heated offices with inflated salaries emanating from charities as in England unfortunately .

As an English commercial North Sea fisherman I feel very qualified to make these comments

The day we leave the EU or if there was a way to obtain them I would be delighted to buy seal skins to make our own clothing .

Very best regards .

Luckily, Derek, the EU is not a total no-go zone for seal products. Importing them on a commercial basis is banned, but you can still visit Canada or anywhere else that sealskin is used for clothing, and bring them back as personal effects. It will be interesting to see if the UK carries on with the ban once it leaves the EU.

Interesting and fairly well-researched article, I especially enjoyed the bit about hollow caribou hairs, didn’t know about that. But I can’t agree with you on the last point. In fact, I think you’re painfully wrong and you mistakenly assume conservation to be more straightforward than it is. This is a mistake non-ecologists very often make: the underestimate the complexity of these systems and blatantly disrespect the fact that there tend to be good reasons for these laws and guidelines, and that conservation and ecology are a separate field of science for a reason. I’m not an ecologist, but I am a biology grad student, so I know a little bit about this.

You dismissively cite lobbying efforts by animal rights’ activist as if that’s the end of the story, but the momentum behind such groups is fuelled by our history of driving MULTIPLE species to extinction, often through careless overhunting – very often these are species that were extremely abundant at first. Read up on the passenger pigeon, which went extinct as a result of mass hunts meeting its unique population dynamics (basically, it needed large flocks for its life strategy to work). Thylacines, which occupy a similar niche among marsupials as wolves and foxes, used to be prevalent too before they were hunted to extinction. Some species have external factors threatening them even if their numbers are okay, like habitat fragmentation, or climate change (and the latter affects seals, as they’re cold-dwelling marine mammals that are very much dependent on the dynamic of ice coverage in their habitat, and thus on temperature). Finally, even if they’re listed as Least Concern, the fact is that we have no current population trend data for some of these species, so while we expect that there are a lot of them, we don’t know how it’s been developing. This species is abundant, but some drastic shift in its environment (like the marine ecosystem, which seals rely on for food, tipping out of balance due to pollution or climate change or overfishing or what have you) could have its numbers drop drastically within half a decade, and it’s nonsensical to inflict hunting and trapping as yet another source of risk.

Even if all of the above were not a problem, it’s not just about the numbers of the target species, per se. Unless it’s possible to create fur/skin farms for the animal, any hunting or trapping of it in the wild on the scale necessary to satisfy worldwide demand is severely, catastrophically detrimental to the habitat and all the species living there. Sometimes conservation of one species (like the seal) is more about protecting other species by proxy, especially when said seal species is cute, adorable, and easy to win public support for (these two effects, often overlapping, are called “umbrella species” and “flagship species”). A cute species of desert fox may be less in need of protection than some Critically Endangered ten species of lizards or termites endemic to the same area, but by virtue of how our brains are wired, it’s easier to motivate us to protect the little fox than a bunch of lizards. And of course, it’s all tied together. Other species rely on seals for their food, such as predators higher up the food chain, and they may require a specific minimal population DENSITY for the seals to be able to do that effectively. Start hunting seals, and you may endanger polar bears far sooner than you would endanger harp and ringed seals. And at the end of the day, as much as we may know about ecosystems and food chains, we’re still dealing with a chaotic system that we can only predict up to a certain degree.

Conservation is complicated, and the simple fact of it is that harvesting seal skins or the like is a luxury, and it’s not important enough to warrant all the risks of something going wrong and dealing yet more damage to the environment. We’ve already made those mistakes many times, and at this point, with so many human-caused factors driving species to extinction that we CAN’T effectively do anything about, it’s better safe than sorry.

Your eloquence and enthusiasm is well noted. however any species that is plentiful enough to be classified as pests in some places ought to be utilized as a natural, organic, and sustainable product, to be used in place of nylon that is so commonly worn by members of the protest industry. By your definition, natural plentiful, and historically green products worn by thousands of generations of humans, make native and non native people truly evil.

Very glad to learn so much about caribou furs – I’m actually in the market for one for my wife and daughter.

amazing article thanks so much we love!!