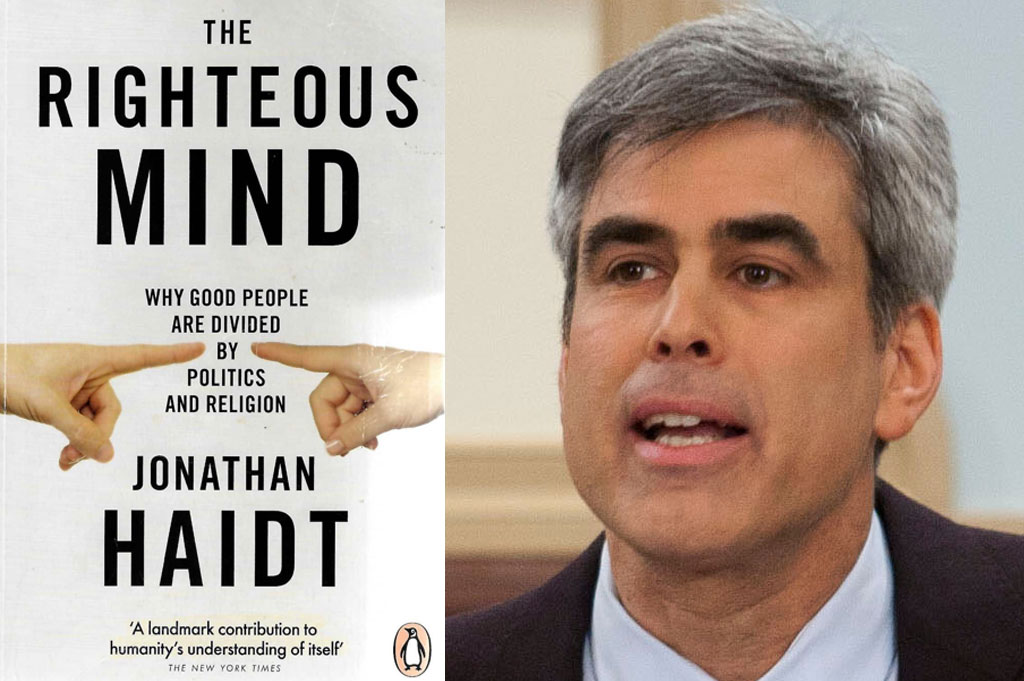

In his 2012 book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, social and cultural psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains why people hold such wildly differing beliefs and why others’ views seem so illogical. Understanding his arguments may be key to reversing the decline in support for various animal uses seen in urbanised societies, and ensuring industries such as the fur trade still have a future.

Ethics (morality) is about the way in which people want to act. Ethics invite us to do the right thing. That there is not always agreement about what is right in a particular case, as for example using animals for food or fur, is due to the fact that morality is partly innate, and partly learned and influenced by the environment (urban or rural) in which someone grows up.

SEE ALSO: Is it ethical to wear fur? Truth About Fur.

According to recent analyses, our ethical behaviour is based on a matrix of six moral modules that have arisen in our brains during our evolution. The trapper in the North, the cattle farmer in the countryside, and the animal activist in the city centre of a Western country, all have a moral vision based on a moral matrix formed by these six universal modules in their brains.

Every society builds its own moral matrix because its moral values, claims, and institutions rest differently on each of the six moral foundations. The moral matrix built in the brain of young people in a hunting culture will be different from those in an agricultural culture, or in a modern industrialized culture where most people live in cities completely distanced from nature. That is why our judgment of whether something is good or bad is partly connected with the human and world vision presented in our environment. The differences in sensitivity to the various six moral matrices explain the different moral visions that individuals take on certain social issues within the same society.

This moral matrix in our brain produces quick, automatic gut reactions of sympathy or disgust when certain things are observed. These then lead to a judgment as to whether something is good or bad. First comes the feeling, then comes the reasoning.

Haidt describes this by using the metaphor of an elephant and its rider. The elephant represents our automatic intuitions. This is about 99% of our mental world, the part that has been around for a very long time where the automatic processing of information, including emotions and intuition, happens. Evolutionarily speaking, the rider has only recently joined.

When Homo sapiens developed the capacity for language and reason during the last 600,000 years, the automatic processing circuits in our brains didn’t suddenly stop and allow themselves to be taken over by reason. This ensures the controlled processing of information and our “Reason why something is good or bad”. The rider reasons afterwards about what the elephant felt.

The rider (the language-based reasoning) acts as the elephant’s spokesperson, and is very good in making post hoc justifications for everything the elephant has felt. Within a fraction of a second of us seeing or hearing something, our elephant already starts to lean in a certain direction, and this tilt to a particular side influences what we think and say next. By leaning to one side, the rider has little or no interest in the other side of the story. After all, his function is not to find the truth, but to seek arguments to explain why the elephant leans to one side.

The metaphor of the elephant (automatic intuition) and its rider (reasoning), stating that the rider is at the service of the elephant, does not mean that we never question our intuitive judgments. The main reason we can change our minds about moral issues is through interaction with other people. After all, while we are very bad at finding evidence that undermines our own beliefs, others are happy to do this for us, just as we are quite good at finding fault with the reasoning and beliefs of others.

If we want other people to be open to our side of the story, we must first tilt their elephant to the other side. This is not possible by using rational arguments alone. We must look for something emotional, something that acts on their gut feeling, that makes their elephants lean to our side and opens their minds to our arguments. Animal activists, like all populists, are very strong on responding to the gut feeling of the people and make sure that the elephant leans to the side they want. Lies and deceit are not shunned by these people. Just think of the notorious staged video, in 2005, of a raccoon dog being skinned alive for its fur.

The animal-use sector has a much harder time appealing to people’s gut feelings. In an urbanized society, more and more people are developing a moral matrix that is intuitively negative for this sector, in large part because of propaganda from animal activists. The fur trade, for example, has endured this negative propaganda for fully 40 years. The impact of this propaganda on the general public can be explained in the same way as advertising: tell someone a thousand times that food X is healthy, and after a while he or she will be intuitively convinced of that fact. Therefore, it will be vital for the fur trade to find that emotional gateway to open the elephant to our arguments.

Fur checks all the boxes: production is sustainable, animal welfare standards are high, businesses are small and artisanal, and the end product is natural, long-lasting and biodegradable! But as long as we cannot hit the gut feeling of the general public growing up in the city, our rational arguments will fail.

What Are the Six Moral Modules, and Which One Guides the Animal Rights Movement?

Jonathan Haidt summarises his six moral modules as follows:

“1. The care/harm foundation: evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of caring for vulnerable children. It makes us sensitive to signs of suffering and need.

“2. The fairness/cheating foundation: evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of reaping the rewards of cooperation without getting exploited. It makes us want to see cheaters punished and good citizens rewarded in proportion to their needs.

“3. The loyalty/betrayal foundation: evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forming and maintaining coalitions. It makes us trust people that are team players and hurt those who betray us or our group.

“4. The authority/subversion foundation: evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forging relationships that benefit us within social hierarchies. It makes us sensitive to signs of rank and status and to signs of other people behaving or not behaving properly, given their position.

“5. The sanctity/degradation foundation: evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of the omnivore’s dilemma, and then to the broader challenge of living in a world of pathogens and parasites. It makes it possible for people to invest objects with irrational and extreme values which are important for binding groups together.

“6. The liberty/oppression foundation which makes people notice and resent signs of attempted domination. It triggers an urge to band together to resist or overthrow bullies and tyrants.”

Since the sensitivity to each of these six moral modules is not the same for everyone, everyone possesses their personal intuitive moral matrix. For example, there are people who are extra sensitive to the caring/harm, fairness/cheating and liberty/oppression foundation, but usually little sensitive to the loyalty/betrayals, the authority/subversion and the sanctity/degradation foundation. There are also those who have a more spread sensitivity on all six moral foundations, and whose sensitivity for the first three foundations is less pronounced as compared to the first group.

There are also people whose moral matrix is triggered on almost only one module. These then become moral extremists who have a principled ethic. The convinced animal activist is such a person. Everything is reduced to one principle and everything else is irrelevant in their eyes.

The ideologically driven animal activist has a very pronounced sensitivity to the liberty/oppression foundation and not, as we might expect at first sight, to the care/harm foundation. The latter is the case with people who are committed more to animal welfare and who believe that people should be allowed to use animals for human purposes.

SEE ALSO: Animal welfare vs. animal rights: An important distinction. Truth About Fur.

In the first sentence of the introduction to his 1975 book Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals, Australian philosopher Peter Singer writes: “This book is about the tyranny of humans over animals.” Further in his introduction, he states that he “does not feel any love for animals”, but that he wants to end oppression and exploitation, wherever they may occur.

The animal rights activist plays with the general public on their care/harm foundation but their own motivation is the liberty/oppression foundation and their goal is therefore an end to the use of animals for human purposes, not animal welfare. Animal welfare is just the lubricant used by this movement to help it in its attempt to force its moral vision and way of life upon us.

The strength of this animal rights movement is the moral conviction that they are fighting a right fight.

However history shows that moral convictions can have enormous practical consequences. A recent example is Marxism. Marxists saw their beliefs not merely as personal views, but as absolutely certain scientific knowledge. Their socialism thus became “inevitable” and they had the future on their side, as it were. “History is on our side,” they liked to say. Their enormous self-confidence made them very intolerant of dissenters. Seventy years after Karl Marx’s death, about a third of humanity lived under regimes that called themselves “Marxist”. Instead of the expected ideal and just society, Marxist rule produced poverty and tyranny. When it became clear that the facts did not agree with Marx’s theories, so-called “revisionism” arose. Several Marxist thinkers tried to match Marx’s theories with the facts — and the facts with Marx’s theories.

Marxism was a stunning phenomenon because its ideas triumphed while on a practical level it failed permanently and the societies it spawned collapsed or eventually turned away from their Marxist policies.

In this area I see parallels with the animal rights movement and its leaders. They are also firmly convinced that they are right, and regard animal rights as a logical historical extension of rights for ethnic minorities and women, although this comparison does not hold. They also claim that acceptance of animal rights is “inevitable”; it is only a matter of time before anyone who disagrees sees the error of their ways. They also claim that their ideology is scientifically substantiated. And they, too, often adopt an intolerant attitude towards philosophies of life that do not fit their needs. Their views on animal rights are not open to discussion. The appearance of being open to collaborating with others is only part of a deliberate strategy to create a society free of all animal use.

The animal rights movement calls its own principled statement – that animals have the right to be left alone and live freely and undisturbed – the only morally correct position. To live up to this statement, it must curb the freedom of the human animal. Freedom of choice, inherent in being human, must be limited by law to the choice of those who claim to defend the freedom of all animals!

Wanting to apply the principle of moral equality also to beings who have no morality leads to absurd situations and takes us far from reality. It is very easy to point to an animal from a privileged situation and say, “We are not going to use that anymore”, but all things considered, such a method is worthless.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.